Covid-19 was a health crisis, the likes of which the world had not witnessed in over a century. In India, the health crisis was compounded by a humanitarian crisis triggered by the mass exodus of migrant labour. In this narrative, I describe how Karnataka coped with the migrant crisis during the second wave in 2021.

To set the context, by 2021, the department of Labour had struggled with the strains and constraints of 2020. Union representatives, volunteers and labour officers had worked round the clock to ensure food, shelter and safe passage. Like other states and other departments of government, however, Karnataka too had faced brickbats from the media, the courts and the critics. But the ordeal by fire, in a way, prepared us for what 2021 threw at us.

Early 2021 heralded the trickle of returning migrants, particularly to construction hubs such as Bengaluru and Belagavi, and the return of intra-state migrants from their homes in Bijapur or Bagalkot; this trickle soon turned into a stream.

The second wave coincided with my joining the department of labour. My first action as Secretary was to meet my clientele – the workers. Their reaction should not come as a surprise to an informed audience. While they did thank the government for the cooked food and other measures, their primary demand was for work. “Naavu Kelasagaararu”, they said, “Namage Kelasa Kodi, Pagaar Kodi”. (We are workers, give us work, give us wages).

With the builders of our nation

With the builders of our nation

Our strategy for immediate redress was two-pronged — to constituteone, Policy, and two, Practice. The State Disaster Management Authority decided to allow in-situ construction to continue. This ensured steady work and income for construction labour, which formed the bulk of our labour force. Other industries were permitted with limited work-force and staggered timings.

Auto rickshaws for awareness programmes in labour colonies

Auto rickshaws for awareness programmes in labour colonies

But this bold policy measure also placed the onus on the department and the industries to put preventive safeguards in place. Here, we focused on continuous sanitization and fumigation of workplaces and labour colonies. Most industries took on the responsibility of testing within their campuses and premises. But in the medium term, we had to carry out vaccination as well.

Vaccination Drive

Vaccination Drive

Again, most industries including garment industries took up vaccination of their workers. But in vaccinating the real estate sector, we faced an unexpected obstacle. In the early months, you will recall, vaccine was in short supply. The Vaccination Monitoring Committee, headed by the Chief Secretary, therefore directed our department to arrange vaccination by private hospitals on purchase basis. But before we could begin that process, the trade unions objected to using the Construction Board funds for vaccination and insisted that government funded vaccine should be used, free of charge. For a while, we were worried as this would delay the vaccination and thereby endanger the safety of workers. Fortunately, the vaccine situation eased, and we were able to tie up with the state government and ESIS hospitals to vaccinate the workers.

Announcement of cash relief on Hon. Chief Minister’s Twitter Page

Announcement of cash relief on Hon. Chief Minister’s Twitter Page

During the second wave of Covid-19, the state government announced two main types of relief measures — cash relief and dry ration kits. Cash compensation of Rs. 3,000 was announced for each registered construction labour, and Rs. 2,000 each for unorganized labour. This followed the Rs. 5,000 compensation that had been announced in 2020 for specific categories of unorganized workers such as barbers and washermen. An amount of Rs. 582 crore was extended to nearly 25 lakh construction workers and Rs. 240 crore to 12 lakh unorganized workers as one-time cash relief.

Cash Relief announcement in the media.

Cash Relief announcement in the media.

The media recognized that the Labour department was the first to operationalise the distribution of compensation by Direct Benefit Transfer. Learning from the cumbersome 2020 experience of distributing cooked food, we opted to distribute 28 lakh dry ration kits and 21 lakh sanitary kits, both of which were well received. The announcement and distribution of cash compensation also had a collateral effect of increasing registrations of both unorganized and construction workers. While this put an additional burden on our officers, it had a salutary effect overall.

E-Shram Registration drive to increase coverage

E-Shram Registration drive to increase coverage

We collaborated freely and shared transparently – NGOs, Unions and people’s representatives all participated in the effort. Those who started out as critics, soon became partners and participants. We did the work and moved on, never seeking credit or publicity, and in time, people acknowledged this approach.

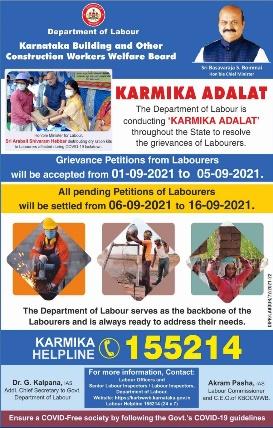

Distribution of dry ration kits & Karmika Adalat

Distribution of dry ration kits & Karmika Adalat

We already had a functional helpline, which we used as an awareness creation tool, along with advertisements, posters and auto rickshaw announcements. To deal with complaints, we constituted a redressal committee of senior officers. Our own internal communication was over phone, WhatsApp and daily video conferences.

Procuring precious oxygen for our patients

Procuring precious oxygen for our patients

All was not smooth sailing, though. Delay in the movement of oxygen cylinders on the highway created hours of high tension until my Director, Factories & Boilers, personally escorted the oxygen truck to the ESIS hospital. An isolated instance of an error by the helpline earned us the wrath of the Chief Justice of Karnataka, which was finally resolved by additional training and a policy tweak which enabled domestic workers to get certified by their domestic employers. But by and large, the experience was positive, which was even more apparent when our sternest critics, the Unions and the state MLAs, both appreciated our efforts.

The pandemic and the lockdowns — this is the context we address. And yet, our most important learning is that our efforts to address the migrant crisis could not stop with the pandemic and the distress related to the lockdowns alone. It had to go beyond that and strengthen the self-reliance and the resilience of the community of workers to face, and overcome, the challenges on a long-term basis. So, while we focused on immediate relief, over the last year we also seamlessly dovetailed it with long-term welfare measures. Thus, the pandemic became the trigger for a slew of measures that included healthcare, education, and social security. We enhanced medical reimbursement and enabled Covid claims.

Mobile Health Clinics

Mobile Health Clinics

As a preventive health care measure, we are now carrying out health camps at labour colonies and clusters where 21 defined medical tests are conducted for diagnosis and disease prevention.

Launching the IAS/KAS Coaching Centre for Construction Workers’ Children

Launching the IAS/KAS Coaching Centre for Construction Workers’ Children

We enhanced educational assistance, covering the fees for higher education for the children of construction laboureres including for Civil Services Exams training, and full reimbursement of fees, including application fees, for professional education in national institutes such as IITs, IIMs, NLSs and so on.

Sharing the Karnataka Experience in the UN Migration Summit, New Delhi

Sharing the Karnataka Experience in the UN Migration Summit, New Delhi

The journey goes on. We learnt from our mistakes, but more importantly, we anticipated and learnt to avoid or quickly resolve them. Most of all, we are grateful for the support we received, from trade unions, industries, the union government, the media and the workers themselves, and the opportunity to lay the long-term foundations for the economic and social stability and development of all workers.

Dr. Kalpana Gopalan, IAS, is a composite public policy professional – practitioner, policy-maker, scholar, author, volunteer and mother. Her 35-year cross-sectoral public service experience is enriched with a Doctorate and Masters in public policy from IIM Bangalore. Her views are personal, and for academic purposes only.