I first heard about Nandini Vijayaraghavan a couple of years ago, when a friend of mine forwarded a short review of her translation of Shri Krishnamoorthy’s Tamil classic, Sivakamiyin Sabadam (Sivakami’s Vow). Tamilians of my generation, and that of my parents, grew up waiting for serialized version of this and his other novels in the Tamil weekly, Kalki.

You can get a glimpse of Shri Krishnamoorthy’s life and work at https://www.thehindu.com/books/how-kalki-penned-ponniyin-selvan-dipping-into-archival-books-in-an-old-steel-trunk/article65949508.ece and https://www.thehindu.com/books/kalki-krishnamurthy-his-life-and-times-more-than-just-a-biography/article65296015.ece

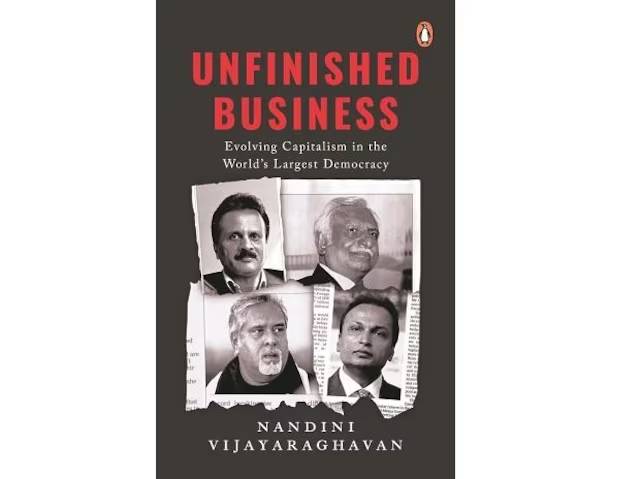

Unfinished Business is no work of fiction, although as Vijayaraghavan notes in the book, quoting Aldous Huxley, “Reality never makes sense.” The book is a chronicle of four businessmen who grew their businesses rapidly, in an endeavour to ascend to the top echelons of Indian business. They came crashing just as quickly, ascent and descent all in the course of one lifetime. All examples of “Icarus entrepreneurship”, flying on the “paraffin wings of debt and political connection”.

The businessmen featured in the book are V G Siddhartha (VGS) who, among many things, set up the Café Coffee Day chain through the Coffee Day Enterprises Ltd. (CDEL), Naresh Goyal, founder of Jet Airways, Vijay Mallya, the scion of the UB group set up by Vittal Mallya, and Anil Ambani, brother of Mukesh Ambani and son of Dhirubhai Ambani.

More than the chronicles of four businessmen

Vijayaraghavan’s chronicle is not just that of the four businessmen and the enterprises they set up. In extending their stories to that of the industries the businesses were a part of – aviation, defence, telecom, and oil and gas – Vijayaraghavan gives herself a much larger canvas to paint on. She traces not just the developments in the industries, but also dwells at length on the interplay between public and industrial policy and business.

She travels down many related paths, in the typical Indian mythological tradition of weaving a network of upakathas (subordinate narratives) that branch off from and come back to the main narrative. Take for example, the financial trouble that CDEL ran into in 2018 that eventually culminated in the tragic death of VGS. It was due to its difficulty in raising debt funding. But Vijayaraghavan uses that pretext to describe the origins, growth and the eventual, catastrophic collapse of Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services, more popularly known by its acronym IL&FS.

The sad saga of the Indian aviation industry and India’s pre-eminent business group

Similarly, her narration of the stories of Vijay Mallya and Naresh Goyal, presents a brilliant summary of the Indian aviation industry, starting from the time 28-year-old JRD Tata flew a Pussy Moth belonging to Tata Air Mail, in what was the maiden flight of the Indian aviation industry in October 1932, all the way forward to Air India returning to the Tatas in 2022, after 70 years of turbulence and policy driven mismanagement under the ownership of the government.

Vijayaraghavan’s narrative covers all the drama, and the numerous twists in the tale, including the alleged manoeuvers by Naresh Goyal to advance the interests of Jet Airways by causing harm to the business of its competitors. In the end, it is a long and sad saga of imprudently excessive leverage, the unhelpful role of the government, including in the pricing of air turbine fuel and/ or poor governance.

Unfinished Business is also a story of the restructuring of the ownership of the largest Indian business group, between the two brothers Mukesh Ambani and Anil Ambani. Here again, Vijayaraghavan dwells at length on the telecom wars, the games that operators in the oil and gas industry played, the origins of the Reliance empire and the terrible, bitter rivalries that it outlived to emerge as the corporate juggernaut that we know it as today.

Raconteur and credit analyst rolled into one

Vijayaraghavan combines the rigour of financial scrutiny of the credit analyst that she is by training, with the wit and literary style of a writer of fiction, to deliver thumbnail sketches of the evolution of the companies and industries she covers. Her attention constantly turns to the high level of borrowings of the companies and how they eventually did the companies in. Her narratives are peppered with financial detail. Interestingly, in her prologue, she laments that she had to renege on her initial thought of writing this narrative without any numbers in it.

That analysis alone renders a near textbook-like quality to her work. Stories of the kind that authors like Vijayaraghavan write is where the rubber meets the road, to use a cliché. Managers of finance can learn from these stories how to marry business strategy and financial management and deploy the underlying economic theories that business schools teach with great enthusiasm.

Takeaways from Unfinished Business

My takeaways from Vijayaraghavan’s analyses are essentially as follows.

First, companies should pursue growth that is financially sustainable. They should be engaged in businesses which produce cash flows that are sufficient to finance their growth to a substantial degree, if not entirely, instead of having to borrow to grow.

Second, businessmen who intend to leverage their political connections for business advantage need to keep in mind that politicians are “fair weather friends”. Political leverage is rarely a sustainable competitive advantage.

Third, companies should borrow only as much as their cash flows can repay, even where there is a financial downturn for the borrower.

Fourth, companies should adhere to good canons of governance that treat all stakeholders fairly. A common theme running through all the four principal narratives and the related subordinate narratives is one of how corporate governance in Indian industry is still far from being fair to various stakeholders. Vijayaraghavan notes instances of questionable governance even in firms that have been darlings of the stock market such as Inter Globe Aviation, the company that operates Indigo Airlines.

Vijayaraghavan has many more things to say. I would encourage you to read the book to know what they are.

A tour de force, almost…

Net net, Unfinished Business is an impressive work. It would have been a tour de force, if it was not for the following reasons.

First, Vijayaraghavan must have had good reasons for her pronouncements about borrowing levels being high and so on. A little background on what makes a given level of debt too high or too low, in relation to any accounting parameter, should help many non-finance readers understand her observations better.

Second, her style of narration occasionally resembles the unravelling of the plot in a Poirot mystery. The reader has to follow the trail of narration carefully to understand the plot. For an ageing brain like mine that was a challenge alright.

Let me give an example. She travels back and forth in time to describe the financial travails of R Power when she describes their dependence on Reliance Petroleum for feedstock gas and then the IPO, and then comes back to the various challenges that affected the contractual pricing of the gas. Would it have been possible to arrange the narration differently?

Finally, at the risk of nitpicking – and I hope I can be forgiven for doing so, given that I am a pedagogue – I am not entirely persuaded by her comparison between Anil Ambani being trapped in a house of debt, which he had created himself in large measure, and the Pandavas trapped in a house of lac (“Lakshagriha”). No matter how limited, the comparison just does not stick. The two have little in common.

A must read for every student of business in India

All of that said, I believe that every student of management programmes in India ought to read the book. If not the whole of it, at least the last chapter titled ‘Knives Out’, and the Epilogue. The book is an illustration of how an analyst has to travel far afield, beyond what the annual reports and financials tell us, in order to understand the prospects for a business. Developments in corners an analyst might never imagine can potentially hold the keys to the future of the enterprise.

As for me, I hope to read it again, once I retire. I love Vijayaraghavan’s book for the walk down memory lane that it is to me. Over my 40-year life in the world of finance and management I have run into most of the protagonists in her chronicles. And those I have not engaged with professionally, I have followed them diligently through the financial press over the years.

G. Sabarinathan, PhD, teaches at IIM Bangalore. He is currently busy counting the number of monthly pay cheques he will receive before he retires. He does occasionally lose count of them.

Interesting critique