By

Professor G. Sabarinathan1

Ever since its first attempt at an Initial Public Offering (IPO) was dropped, news about the developments at the highly visible co-working space provider, WeWork, later on rechristened as The We Company started tumbling out in the form of numerous press stories. Books were written about its meteoric rise and the equally visible crises it descended into.

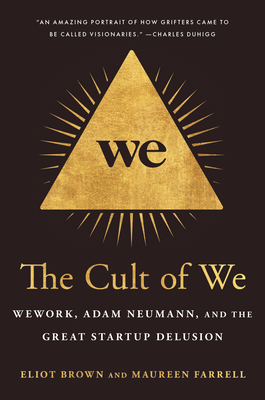

This article is based on one such book, The Cult of We – WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell2. Both Brown and Farrell had been tracking the evolution of the company for the Wall Street Journal for many years.

The book itself is somewhat on the lengthy side, at 400 plus pages, in the edition I read. Even with less real estate devoted to the not so commendable interests of the founder, Adam Neumann, such as substance abuse on a grand scale, the many residences that he acquired, the various vanities of his wife Rebekah Neumann and so on, the reader can get a sense of the personal lives led by the Neumanns and their hopeless style of managing the enterprise.

Brown and Farrell provide a detailed picture of the many wrong turns that the founders took while growing the enterprise – in terms of strategic direction, pursuing growth in sales at the expense of profitability, the management of people and corporate governance.

The story of WeWork’s evolution is worth knowing in some detail, even if it be boring and all too predictable for those who have read accounts of corporate misgovernance in other enterprises in the past. It is the equivalent of salacious gossip from the world of startups, even if one does not see any object lessons worth learning from it.

The part that investors played

It is generally believed that venture capitalists (VCs) bring great discipline into evaluating investment opportunities before committing funding or managing their investments once funding is committed. WeWork, in contrast, appears to have been as much a product of inadequate diligence on the part of those investors who shovelled barrel loads of money into the venture in seeming recklessness. WeWork was funded by some of the best names in the world of VC and private equity like Benchmark and Goldman Sachs.

Take for example, the idea about WeWork as a technology-driven enterprise, notions that Neumann managed to successfully convince investors about. The reality was that “WeWork’s tech was hardly cutting edge. The company was struggling to put together a basic billing system let alone build a killer app.”

Or, take the other claim that Neumann constantly pitched that WeWork was “like Uber and Airbnb”. Investors “focused on the few parallels between those businesses rather than numerous fundamental differences including how Airbnb and Uber are asset light.” More importantly, Uber and Airbnb did not have “costly 15-year leases for their homes and cars.”

In short, as the authors write, “In a world awash with cash, these investors feared missing out on the next big highly lucrative idea. More often than not, the risks were brushed aside.”

Unrealistic goals, unconscionable burning of cash

VC investors insist on “staged investing”, a practice in which capital is released to the entrepreneurial firm in stages, tied to the progress of the enterprise. That results in a certain parsimony in spending capital. One article even glorifies such parsimony as “the power of penury”. WeWork and its investors threw such prudence to the winds. The more WeWork lost the more its investors appeared to be happy to fund it, as long as it was backed by the pursuit of ambitious targets, no matter how unrealistic such goals may have been.

In 2016 the company was losing a million dollars every day. Over a six-year period, it had come a long way in burning cash from having spent barely a million dollars in the whole of 2010. The book is with replete with instances of how WeWork burnt cash in unproductive avenues like its annual Woodstock style get together where people freely smoked various herbs, Neumann’s fancy for private jets and expensive liquor, discarding costly interiors bought for doing up their co-working spaces by their whimsical designers, ill-planned, unrelated acquisitions that turned out to be worthless and so on.

Enter Masayoshi Son

Epitomising this world view of investing was Masayoshi Son and the investment organisation he had created in Softbank. The authors’ description of Son’s style of investing is illuminating and interesting at once and is worth quoting in full.

“Son would meet the entrepreneur in an office or one of his mansions in Tokyo or California sometimes giving a tour, showing over-priced painting of Napoleons he owned. He would then ask about the business and the funding that the entrepreneur sought. If the founder said he wanted $150 million, Son would respond that he was not thinking big enough. That he needed to double growth, even if he did not know much about the company or industry….Eventually in the span of the brief meeting, sometimes just twenty or 30 minutes long, Son would persuade the founder to take a larger cheque. The $150 million request might turn into an offer for $500 million. If the founder seemed reluctant the offer could turn to a threat. Son would point to how he could find rivals if the founder refused his money. Losses were rarely discussed.”

Egged on by Son, Neumann’s delusions just seemed to get grander and grander. With the former’s assurance that he would have unlimited access to Softbank’s capital, including his newly raised Vision Fund of US $ 100 billion, the latter dreamed a future where WeWork would manage one billion square feet of real estate, “more than twice the size of the entire Manhattan office market.” WeWork’s goals was to generate a revenue of $101 billion, up from $ 2.3 billion in 2018!

Valuation – the kicker

Throughout this heady evolution, Neumann seems to have been driven by the quest for an ever-growing upward spiral of valuation. From a $ 45 million valuation in 2010, when it raised the first round of significant external funding of $ 15 million, by 2016 WeWork had reached a valuation of US $ 10 billion, achieving the status of a decacorn.

At that valuation WeWork was worth roughly $ 300,000 per member3 or 50 times its 2015 revenue. Regus, a more traditional office renting company that was profitable, was valued at $10,000 per member at the same time, which was less than two times its revenue.

At every stage, as WeWork raised more and more capital, Neumann was intensely focussed on scaling up the valuation by a huge factor from the previous round. With Softbank on board, Son and Neumann seemed to be eyeing a valuation of $ 10 trillion at one point in time. Often, these valuations had little connection with reality. It was simply based on Neumann’s illusory notions of what WeWork was and beliefs about what its valuation ought to be.

Visions of grandeur

As striking as the pursuit of spiralling valuations was the vision of grandeur that Neumann seems to have harboured, nurtured and frequently articulated. Neumann visualised a future where WeWork was “ubiquitous across the globe, providing all aspects of society and the economy.” It eventually led him to rename the company The We Company.

Not just that. Neumann began to aspire to make the world a better place. He actively sought audience with political leaders across the world.. He parlayed with the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, on ways in which WeWork could contribute to the development of the Indian entrepreneurial ecosystem. At one point, Neumann is supposed to have told Prince Mohammed Bin Salman of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, “You, me and Jared Kushner are going to remake the region.”

But Neumann was not alone in nursing such delusions of grandeur or being driven by a messianic zeal. He seemed to be following in the footsteps of other iconic founders of high profile start-ups in Silicon Valley, such as AirBnB, Uber and Peloton, who had made similar statements about wanting to remake the world.

Failure of Governance

Needless to state, the biggest casualty of the grandiose and unrealistic plans, was governance at WeWork. The board at WeWork was weak and pliant. In the early years, they seemed to be in awe of Neumann. With the passage of time, they turned into helpless spectators as he introduced one measure after another that perpetrated his hold over the firm. By the time the board realised that Neumann had no regard for good governance, it was too late and nearly impossible to rein him in. Neumann was already an entrepreneurial train wreck, fuelled by Son’s money.

Neumann kept cutting real estate deals on the side that benefitted him, even as he negotiated property deals for the company. He consummated financing deals that increased his control over the firm and presented them as fait accompli to the board, even though he had nominees from among his investors on his board. At the end of one such deal with Fidelity, he had accumulated so much voting power on the shares he held that even if had only 5% of the equity he would still be in full control.

By the time the red herring prospectus was ready to be filed Neumann had also made himself a permanent CEO, given Rebekah a prominent place in the company despite the questionable value she brought in and had put in various other provisions that made institutional investors extremely uncomfortable. The We Company looked like an investor funded and owned, Neumann family-controlled private enterprise.

WeWork: Symbolic of an Emerging Ecosystem?

The story of WeWork appears to be a part of a larger phenomenon in the start-up ecosystem. Brown and Farrell provide an amusing, even if somewhat oversimplified, account of the ecosystem in the Valley around that time that resembled a full self-contained economy of its own, funded by generous VC investors.

“The city quickly became a terrarium of money losing start-ups” they note. Employees of VC-funded start-ups would line up for lunch at VC-backed salad purveyors, stop for coffee at VC-backed coffee shops, wearing VC-backed sneakers, get rides well below cost from unprofitable VC-backed ride hailing companies, park their cars below cost with unprofitable parking solution providers and so on.

The End of VC Investing as we knew it?

Competent early stage investment professionals bring certain skills and capabilities that play a useful economic role in financial markets. They help allocate capital efficiently to opportunities in private equity. They bring good quality enterprises that are competitive, well managed and well governed to the public equity markets. Academicians refer to this as certification value.

Reflecting on the role that the investors in WeWork played makes one wonder if any of that mattered any more in the brave new world of early stage VC investing. Or, have we transitioned to a world where, as the authors note, all that investors have to do is to hand over their money to “well-spoken entrepreneurs with a strong vision, someone who could not only come up with an innovative idea but also, crucially, sell it to others.” Have we embraced the religion of “worshipping at the altar of the founder”? Are we witnessing a culture that the authors refer to as the “cult of the founder” that has been typified by the likes of Dorsey, Chesky, Musk, Kalanick and others of this age? An age that probably started with the struggle for power between investors in Facebook and Zuckerberg, as recounted by David Kirkpatrick, in his book, The Facebook Effect-The Real Inside Story of Mark Zuckerberg and the World’s Fastest Growing Company.

In such an age, what happens to all the lessons on early stage investment management that practitioner accounts as well as academic research try to impart to future generations of aspiring investment professionals? The story of WeWork makes one wonder about the relevance of those competencies in the contemporary world of investing.

Post Script

The story of WeWork had a bitter-sweet ending as Son took control of the enterprise after the failed IPO and the near implosion it caused. Neumann lost his job as CEO and founder. That was the bitter part. The sweet part of course was the severance package that he negotiated that will go down in corporate history for its sheer egregiousness. He walked away with a billion dollars in cash, a loan of $ 500 million, according to the authors. A Wiki write up reported that he received close to $ 1.70 billion in compensation in addition to an annual salary of $ 46 million as a “consultant”. And Neumann is reportedly putting all those riches to good use, yet again, in an attempt to disrupt the rental market.

1Professor G. Sabarinathan teaches Finance at IIMB. He used to offer an elective course on early stage investing. Views in this piece are personal.

2This article is based on the 2021 London:Mudlark edition of the book.

3Members were WeWork’s tenants.