How I came across the book

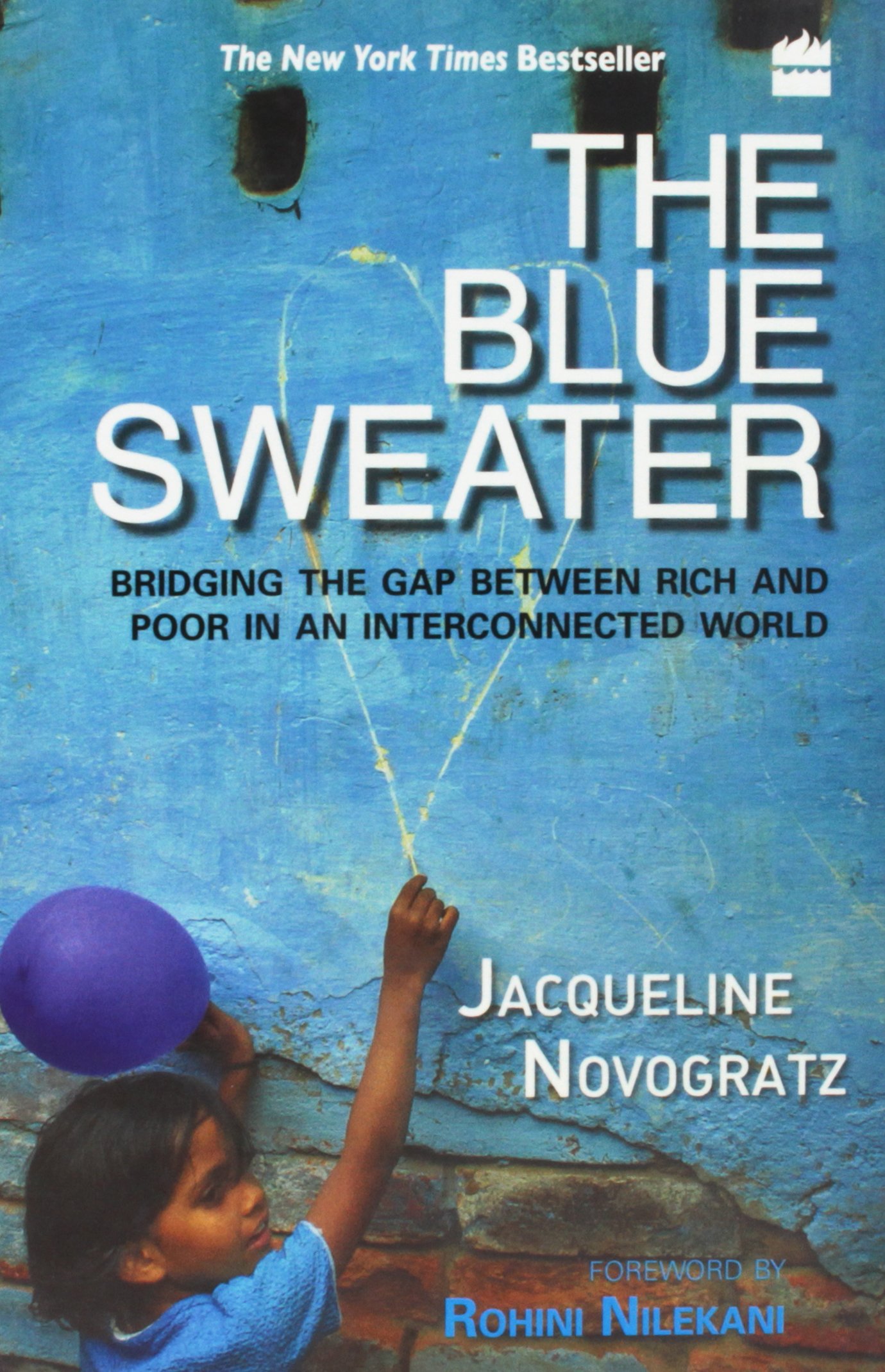

As the year draws to a close, like a slow batsman trying to add a few lucky runs in the last few deliveries remaining in a limited over match, I managed to finish reading one more book: The Blue Sweater, by Jacqueline Novogratz.

I had heard of Novogratz as the founder of the Acumen fund when I had been invited to a dinner with a few Acumen fellows a few years ago. My engagement with impact investing then – and to a large extent even now – was less than that of even a curious bystander. I was at the dinner more to please a mentor at the entrepreneurship centre I was managing back then.

More recently my disposition towards impact investing drifted just a wee bit towards intellectual curiosity during this year as I struggled to write a case on an impact investment fund. The case never saw the light of day, but I must have plodded through more than 1500 pages of literature to understand the phenomenon.

It was in this backdrop that the reference engine at Amazon serendipitously pushed Novogratz’s book towards me. The reviews were all glowing, without an exception. Her book seemed to have all the ingredients of Malayalam movies that I gorge on – humour, pathos and so on. I set a career best record of sorts when I swept through 310 pages in less than a week.

The burden of the book

The book is mostly autobiography and in large part also an account of her life as a development professional. As a trained bean counter, I believe the real estate devoted in a book is a measure of the relative emphasis laid on specific themes in the book.

By that measure 214 out of the 310 pages in the edition I read are devoted to her life and work in Cote d’ Ivore, Rwanda, Kenya and Gambia as part of UNICEF and the World Bank. A large part of this in turn narrates her setting up Duterimbere, which went on to become one of the more successful institutions of Africa.

Novogratz’s world view on development

Way back in 1987, when Novogratz quit her well-paying job at Chase Manhattan Bank as an international credit analyst, the West was choosing between philanthropic giving to the third world and development loans to governments of these countries as a means to redeeming their people from poverty. Novogratz seems to have been clear in her mind even back then that empowering the poor to be able to earn a living with dignity by supporting the creation and working of markets would be the only sustainable way to pull the poor out of poverty.

She further seems to have believed even back then that empowering women would not merely restore the sorely missing dignity to women, but also have significant collateral social benefits for children and society at large. A theme that is now very much in vogue in the discussion on women entrepreneurship.

She seems to have stuck to that belief all through the forty years of her work in that space that the books travels through. Throughout the many stories of entrepreneurship that the Acumen fund supported in India, Pakistan and Tanzania, her heart seems to beat for the status of women, lamenting their plight inspite of the economic development that some of the Acumen funded projects pull off.

Novogratz’s favourite themes

The constant theme that she keeps coming back to in the book is that of moral imagination. For those who may not have heard of it earlier, the philosopher Mark Johnson notes that it calls for “empathy and the awareness to discern what is morally relevant in a given situation”.

If moral imagination is the leitmotif, there are a few other subsidiary or derived themes that run throughout as well. These are empowerment of women, a belief in market-based solutions that are based on discipline, accountability and market strength and not on what she refers to “easy sentimentality” and the idea of interconnectedness.

The idea of interconnectedness first plays out with her finding her favourite blue sweater that she discarded in Virginia being worn by a boy in Africa, several thousand miles away, whom she would not have known of at all. She brings it up again one last time when she quotes Dr Venkataswamy of Aravind Netralaya as saying, “God exists in that place where all living things are interconnected.”

A remarkable life

Novogratz’s life has been remarkable, playing a pioneering part in whatever she has done. Be it in setting Dutirembere or the Philanthropy workshop she designed at Rockefeller. She also comes across as an adventurer who loves to tempt fate as she did when she hiked up to a volcano in Kenya, completely unprepared.

There is also this other side to her which is hard to comprehend which makes her trace the path back to three key women who had worked with her to set up Dutirembere, but were cast in different destinies by the tragic genocide of Rwanda, to find out about what they had done during the genocide and how they ended up where they did.

Novogratz writes like a poet. Her wide reading is reflected in her luscious prose, full of imagery of all kinds. Her attention to detail is remarkable, whether it be of the surroundings in which her work was set or the dramatis personae. One wonders if she ever imagined that one day someone would want to make a motion picture out of it. And her life’s story clearly deserves to be the subject of an interesting movie, given the moving human element and the picturesque nature she describes ever so often throughout the book in graphic detail.

Towards the end, my extremely cynical eye did get a feeling that either the author or the editors and proof-readers or both were in a hurry to wrap up the book. One is surprised to see “what striked me most” (p 275) and “the last women we met” when what was meant was the singular. Well, yeah I agree I am being really nitpicky here, but then in a strange way to see these little imperfections in what would otherwise have been a too flawless to be true effort.

My learnings

I learned a lot from her book. I learned about the wonderful work that many of the enterprises that she has supported in Acumen are doing. I learned, for example, that social entrepreneurship differs in an important way from more traditional for-profit enterprises: The idea that build it and the customers will come does not work in low income markets. I learned that the traditional idea of philanthropy was mainly about making the donor feel good and less about bringing about sustainable change for the beneficiary. Uplifting people out of poverty, on the contrary, has to be a beneficiary driven process: By the beneficiary, for the beneficiary, to use a cliché, with support and nurturing from the benefactor.

As I reflected on the book after I finished reading it, I feared that I was beginning to be slowly converted into the market-based philosophy of redeeming people from poverty. Am I fully converted yet? Probably not. I am reminded of the Wall Streeter, whom Novogratz approached for raising capital from, who seemed to keep “a strict division between the way they made money and the way they gave it away” and who counselled that “when you try to do both at the same time it will never work”.

I am also worried about how well-meaning economic development can potentially upend the social fabric of a community with its attendant problems. Some of these not-so-favourable changes are wrought so slowly over time that it may be hard to anticipate, even more so to address them, unless one is highly sensitive.

Novogratz’s book is refreshingly devoid of starchy expressions like “theory of change” and “randomized control trial” that made the literature I read on impact investment soporific. Her approach to development emphasizes involvement at the grassroots level, unlike the top down approach of development experts, which she is critical of. That said, some amount of interdisciplinary drawing on the lessons of academic research may help address the potential concerns arising out of economic development, even if driven from the grassroots level.

Dr. G. Sabarinathan is Associate Professor, IIMB.